|

ADMINISTRATION

...The Bamhanī plates give the names of some village officers.1 The Grāmakūṭawas the

head of the village administration. The Drōṇāgrakanāyaka , who also was informed of a landgrant, may have been the head of the Drōṇāgraka (also called Drōṇamukha)2, the larger

territorial division in which the donated village was included. The Dēvavārika, who appatently helped the Grāmakūṭa in the management of the village affairs, may be identical with

the Dauvārika (or Pratīhāra)3, who was the head of the village Police. The Gaṇḍakas were

probably not different from the bhaṭas or soldiers mentioned in Vākāṭaka land-grants.

These officers and their the bhaṭas or soldiers mentioned in Vākāṭaka land-grants.

and maintained peace and order in the village.

...Sources of State Revenue-Our records shed some light on the sources of royal income.

The main sources were of course the land revenue and other direct taxes. They are

mentioned as kḷipta and upa-kḷipta in Vākāṭaka inscriptions.4 Kḷipta, which means a fixed

assessment, is mentioned also in Kauṭilya’s Arthaśāstra5. It probably signified the land-tax. Upakḷipta probably meant minor taxes such as are mentioned in the Manusmṛiti, VII,

131-1326. Besides these, the State claimed the right to confiscate the treasures and deposits

accidentally discovered. Digging for salt was again a royal monopoly. Salt mines existed

in Berar until recent times, Loṇār (Sanskrit Lavaṇākara), a village in the Buldhānā District

of Vidarbha, being specially noted for them. Fermenting of liquors was also a royal pregorative. The village officers were authorised to collect miscellaneous taxes in kind which

are indicated by the expression pushpa-kshīra-sandōha in Vākāṭaka grants7. These were

evidently the same as those mentioned in the Manusmṛiti VII, 118, which the head the

village was authorised to collect on behalf of the king and appropriate in lieu of his pay.

The State had again the right to make people work free of wages for works of public utility.

The villagers had to provide all amenities to touring royal officers, such as grass for feeding

their horses or bullocks, hides for their seats and charcoal for their cooking8. The agrahāra villages were exempted from all these taxes and obligations.

...

We have no record of any dissensions in the Vākāṭaka family as we have in the case

of some other contemporary royal families. The administration of the Vākāṭakas appears

to have been very efficient and it secured peace and prosperity to their subjects. As the

inscription in Ajanta cave XVI states explicity, the ministers of the Vākāṭakas, by their good

government, became always dear and accessible to the people like their father, mother and

friend. They governed the country righteously, shining by their fame, religious merit and

excellences9. In describing Vidarbha as saurājya-ramya (attractive through good government)

Kālidāsa was probably paying a tribute to the excellent administration of the Vākāṭakas10.

________________

1 No. 19, line 35.

2 Kauṭilya mentions Drōṇamukha as the chief village in a territorial division of 400 villages. See Arthaśātra (second ed. by Shama Sastri), p. 46.

3 Pratihara, which is a synonym of Dauvārika, is used in this sense in the Śukranītīsāra, II, 120-21 ;

170-75.

4 See e.g. No. 3, line 28. No. 19 mentions udraṅga and uparikara and also bhāga and bhōga in the

same sense.

5 Arthaśāstra (second ed.), 60.

6

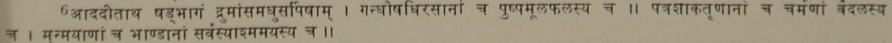

7 See e.g. No. 5, line 20.

8 Ibid., lines 20-21.

9 No. 25, lines 12 and 15.

10 Raghuvaṁśa, canto V, v. 60. In v. 40 of the same canto Kālidāsa describes the capital of Vidarbha

as prosperous (ṛiddha).

|