|

The Indian Analyst

|

North Indian Inscriptions |

LITERARY HISTORY He renders it by “the fame sprouting forth, shining purely like the moon.” This translation, however, is not quite satisfactory. It should have been “(his) spreading fame is as bright as the spreading rays of the moon.” Here śuchi is one word. It should be rendered by either ‘shining’ or ‘pure’, and not by both together, that is, by ‘shining purely’ as he has done. Secondly, sapratānāḥ is taken by him to mean ‘sprouting.’ On the strength of this slender basis, he asseverates that the whole expression “bears evidence to his (Harishēṇa’s) being aware of the well-known idea of the kīrttivallī or the creeper of fame, which covers over the three worlds with its tendrils.” The word pratāna, no doubt, signifies ‘a sprout, tendril’. But Bühler forgets that the compound word sa-pratānaḥ is intended to be taken with both kīrttayaḥ and śaśi-kara śuchayaḥ. It should therefore be rendered by ‘spreading’ instead of ‘sprouting’. Again, it is true, as just remarked, that pratāna has also the sense of ‘sprout’ and that, consequently, pratāninī signifies ‘a creeper’. But to conclude merely from the use of pratāna that Harishēṇa is here adverting to the idea of kīrttivallī is not quite justifiable. To take another instance, sīmantinī is no doubt synonymous with vadhū ‘woman’, but not the word sīmanta. So, from the mere use of sīmanta we cannot jump up to the notion of sīmantinī. The notion of kīrttivallī here is thus a little far-fetched. How, again, can this imagery of ‘creeper’ be made applicable to ‘the rays of the moon’? Bühler does not explain. There is, however, one fault in the body of this poem which Bühler has not noticed. It occurs in line 3 of the verse which reads kō nu syād=yō=sya na syād=guṇa iti vidushāṁ. Here syāt is repeated twice and thus gives rise to the Imperfection called Kathita-pada-vākya. This stanza Bühler alludes to, a second time, to prove that Harishēṇa’s composition does not all belong to the beginning of the Kāvya period. This stanza, like stanza 3, speaks of the brisk poetical activity of Samudragupta. If even a king could be a poet, it means that Harishēṇa wrote at a time when kāvya was in full bloom, and not when it was just beginning to develop. This point, however, we will consider in detail a little further on.

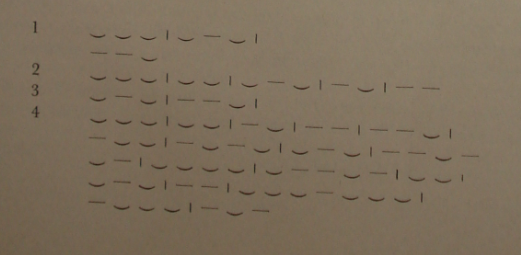

It will be seen that the initial part of the praśasti consists of eight stanzas and covers lines. 1 to 16. Thereafter commences the gadya portion of the kāvya extending from line 17 to line 30. It is comprised of very long sentences which are, nevertheless, so constructed as to permit, to the reciter and the hearer, pauses between long compounds by the insertion of shorter phrases. The views that Bühler has expressed in regard to this prose passage are so convincing that every one of his words will be endorsed by all. His words are worth quoting even though they will make a long quotation. “In the prose part” says he, “there are inserted between the long compounds, at definite intervals, shorter phrases, in order to enable the reciter to draw his breath and the hearer to catch the sense. In the long compounds, the words are so chosen as to bring about a certain rhythm through the succession of short and long syllables; and care is taken to see that this rhythm changes from time to time. This can be best seen by a representation of the design of the compounds occurring in lines 17-22, by marking the accents as is customary in recitation. The lines in question contain only seven long compounds, the arrangement of whose syllables is as follows:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| > |

|

>

|