|

The Indian Analyst

|

North Indian Inscriptions |

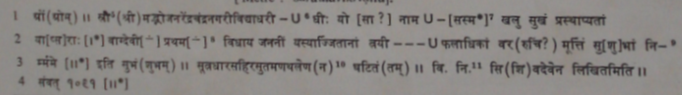

INSCRIPTIONS OF THE PARAMARAS OF MALWA BRITISH MUSEUM SARASVTI IMAGE INSCRIPTION Vāgdevī (Sarasvatī), made of “grey sand stone”, which is now preserved in the British Museum, London, and is a “ typical specimen of Hindu art in the medieval period when it had reached a high standard of perfection”. [1] The inscription is edited here from a photo-copy supplied kindly by the authorities of the Museum, at the request of the Chief Epigraphist, to whom my thanks are due. ...The inscription consists of 4 lines, the last of which is only about one-sixth of the others in

length. No record as to how the image reached the British Museum is now available, except

that it was presented to it by a British officer who obtained it about a hundred years ago in the

ruins adjoining to Bhōja-śālā at Dhār,

[2]

the former capital of the State of that name and now

the headquarters of a district in Madhya Pradesh. The technical execution of the record is good

but it has suffered a good deal from small abrasions here and there, particularly on the proper

left side in 11. 1-3, and an oblique crack on this side has damaged one or two letters in each of the

lines. The base on which the record is incised measures 30.48 by 10.16 cms. The script is

Nāgarī of the eleventh century A.C. to which the record belongs. The initial i, occurring only

once in iti, 1.3, is shown by two curves and placed one below the other ; dh is often formed as v,

e.g. in sūtradhāra, 1. 3 ; the letters t occasionally resembles n, see -nagarī, 1. 1, and –suta, 1. 3 ; and

finally, the curve of v is angular, as in yōsā-, 1, 1. ...The record is in Sanskrit and consists of a dedicatory verse in the Śārdūlavikarīḍita metre, with the portion giving the name of the sculpture and that of the writer and the year in figures in prose, in the end. The orthography calls for the usual remarks, e.g., that a consonant following r is doubled and that the dental sibilant is throughout used for the palatal, for which see nirmmamē and Śiva-, respectively in 1.3. We may also note the throughout use of the anusvāra sign and the pṛishṭha-mātrā .

...The inscription refers itself to the reign of the illustrious Bhōjadēva who is called in it ‘the moon among the kings’ and who has been identified with the great literary person of that name and the kings of Dhārā. The purpose of the inscription is to record the installation of the image of Vāgdēvī, on the pedestal of which it is engraved. The year of the record, as mentioned in figures only and without any further details thereof, is 1091, which is equivalent to 1033-1034 A.C. The sculpture was engraved by Maṇathala, son of the mason Sahira, and the inscription was written by Śivadēva. ...As we know from the Tilakamañjari, the palace of Bhōja or Bhōja-śālā as it is now popularly known, was then called Bhāratī-bhavana on Sarasvatīkaṇṭhābharaṇa ; [3] and the image under reference may have been installed in it, in a prominent place, by Bhōja himself, who was a zealous devotee of the goddess Sarasvatī. TEXT

[4]

[1]See R.P. Chanda. Med. Ind. Sculptures in the British Museum, London, 1936, p. 46. For the description of the

Image, see Gopinath Rao, Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol. I, Pt. II, p. 377 ; and S. Shivaram Murti,

Indian Sculptures, pp. 106 f.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| > |

|

>

|