|

The Indian Analyst

|

North Indian Inscriptions |

RELIGIOUS CONDITION

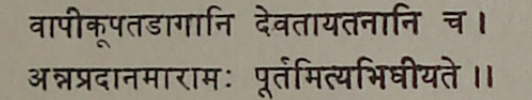

Mahāl of the Kolhāpur District). It was called Tribhuvanatilaka and was constructed by the Śilāhāra king Gaṇḍarādityadēva, who bore that biruda. It is mentioned in the grammatical work Śabdārṇavachandrikā of Sōmadēva.[1] There were two other Jaina temples mentioned in the records of the period. One of them which, like the temple at Ājurikā, bore the name of Tri- bhuvanatilaka, was dedicated to the Tīrthaṅkara Chandraprabha. It was erected at Herle, 11.25 km. from Hātakaṇagale, by Nēmagāvuṇḍa. The Kannaḍa author Karaṇapārya wrote his Neminātha-purāṇa there. The other temple which was dedicated to the Tīrthaṇkara Ādinātha was constructed by the aforementioned Sāmanta Nimbarasa. It is identified with the temple of Śēhaśāyin in the back-yard of the temple of Mahālakshmī at Kolhāpur. From the inscription on the beams on the maṇḍapa of that temple it seems to have been a magnificent structure, large in size, looking beautiful with excellent quarters of merchants and those of courtesans on both sides, a large māna-stambha, and storeyed houses which acquired beauty with gold platings.[2] This description appears exaggerated if it refers to the modern modest structure known as the temple of Śēhaśāyin. On the other hand, it looks unlikely that the ceiling and the inscribed beams of the original temple have been transplanted and used for the present Hindu temple. .. The Smṛitis and commentaries on them held authoritative in this period preach the performance of ishṭa and pūrta for the acquisition of religious merit. Ishṭa denoted Vedic sacrifices, which could be performed only by members of the three higher castes. But pūrta, which denoted charitable works, was open to all. The Aparāka commentary cites the following verse from the Mahābhārata, defining the purta[3] :

[The pūrta includes the following:−construction of large and small wells, tanks and temples of gods, as well as the maintenance of sattras (charitable feeding halls) and gardens.] ..We find from the inscription that the people of the age tried to secure religious merit by means of all these. We have already described the temple-building activity of the age. As an example of the excavation of a tank, we have the mention of the Gaṇḍasāgara dug by the Śilāhāra king Gaṇḍarāditya at Irukuḍi (modern Rukaḍī) in the Miriñja-deśa.[4] References to the digging of public wells occur in some records and to vāṭikās or orchards in many others. Sattras were attached to the temples and maṭhas, where ascetics, students and guests were charitably fed.

..

An analysis of the inscriptions of the age would yield interesting results about the religious

tendencies of the time. Of the sixty-five inscriptions included in the present volume, three are

concered with Buddhism,[5] and six with Jainism.[6] Of the remaining, as many as thirteen

relate to secular matters such as the appointment of a Daṇḍādhipati (Provincial Governor),[7]

royal gifts to officers,[8] royal assent to the claim for a particular village.[9] exemptions from customs dues and from house-tax etc.[10] Of the remaining inscriptions, thirteen record gifts in

[1] Sabdārṇavachandrikā, p. 221.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| > |

|

>

|